State on front line in a trade war

Bay Area could be hit hard if U.S. tariff dispute with China escalates

By David R. BakerChinese officials on Friday announced a list of U.S. imports they will target if their tariff dispute with President Trump erupts into a trade war. It’s a list that places California on the front line.

China’s Ministry of Commerce singled out 128 products imported from the United States, worth about $3 billion annually, that could face higher tariffs if the two countries don’t defuse rising tensions. The tariffs would be imposed in steps, and some of California’s prime exports to China — including nuts, fruits and wine — would be among the first hit. Each would face a new 15 percent tariff.

“When you look at the list of targeted goods and you see how it overlaps with the list of California’s leading crops and commodities, it’s hard not to be alarmed,” California Agriculture Secretary Karen Ross said in a statement.

If the dispute continued to escalate, China said it would impose a 25 percent tariff on American pork and recycled aluminum, a potential blow to Midwestern states considered part of Trump’s base.

But no state exports more products to China than California, or receives as much Chinese investment.

The two economies are closely linked, even though China’s restrictions on direct foreign investment and American Internet companies remain constant sources of friction. So do charges that China’s government tolerates, encourages or may even engage in intellectual property theft.

“It’s a complex and deep business relationship fraught with challenges, only exacerbated by a trade war,” said Carl Guardino, CEO of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, a business association. “Tariffs are like a boomerang that you throw at someone else without always realizing it’s going to circle back to hit you in the head.”

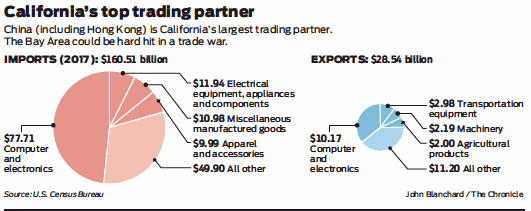

When trade with Hong Kong is included, California exported $28.5 billion in products to China in 2017, according to the U.S. Commerce Department’s International Trade Administration. Electronic equipment tops the list, although agricultural products rank high as well.

At the same time, the state’s imports from China — about $160.5 billion per year — dwarf its exports. But, as is often the case with international trade, the picture is complex. Many California companies — such as Apple, with its iPhones — manufacture products in China and bring them here for sale.

China is California’s third-largest destination for agricultural exports, where more than $2 billion in exports went in 2016, up 18 percent from 2015, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture. In 2016, 46 percent of the state’s exported pistachios, 35 percent of its exported plums, 20 percent of exported oranges and 12 percent of exported almonds went to China.

“We know from experience that agriculture often becomes the victim when it comes to tariffs and retaliation,” Ross said.

Chinese officials released their list of targeted imports a day after Trump announced that his administration plans to slap tariffs on about $50 billion in Chinese imports, both to address the U.S. trade deficit with China and respond to the alleged theft of intellectual property from American companies.

While China is a major customer for California products, Chinese companies and individuals have also increasingly poured investments into the state.

A report last fall from the Rhodium Group, an economic consulting firm, found that California received more Chinese investment in 2016 — $16 billion — than any other state. Much of the money went into real estate and technology companies. For example, Chinese investors have backed California companies developing self-driving vehicles, while Chinese companies pursuing the same technology have opened their own labs in Silicon Valley.

“They employ people here, they certainly are spending a lot of R&D dollars in the state, and there’s the prospect of more to come,” said Thilo Hanemann, who heads Rhodium’s research on global trade and investment.

But that investment in cutting-edge technology under development in the United States has caused concern for the U.S. government, particularly under Trump. This month he blocked Broadcom’s $117 million bid to purchase San Diego’s Qualcomm due to concerns about how the deal could affect America’s technology competition with China, even though Broadcom is based in Singapore.

While the possible tariffs unveiled Friday would not have a major effect on the state, a widening trade war could, according to Hanemann.

“A lot of Chinese companies are going to think twice about investing here,” he said.

With trade tensions between the two countries rising, China’s consul general in San Francisco, Luo Linquan, hosted a dinner for local business leaders Wednesday.

He told them that China planned to further open its economy to foreign products and investment, said Susanne Stirling, vice president of international affairs for the California Chamber of Commerce, who attended the dinner. She, in turn, pressed him on the need for more openness and transparency from his government, she said.

The chamber, she said, would file comments with the Trump administration arguing against tariffs, hoping to avert a full-blown trade dispute.

“We really do recognize that there are issues with some of China’s policies,” Stirling said. “So it’s a delicate balancing act of calling their attention to that without causing disruption to international trade.”

Chronicle staff writer Tara Duggan contributed to this report.

David R. Baker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: dbaker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @DavidBakerSF